New values for modern education

-->

26% of Australian students – more than 1 in

4 – fail to complete year 12 at school or a vocational equivalent, according to

the Educational Opportunity in Australia2015 report by the Mitchell Institute. And the

numbers are worse for those from socio-economically disadvantaged areas and

worse again for Australian Indigenous students.

26% of Australian students – more than 1 in

4 – fail to complete year 12 at school or a vocational equivalent, according to

the Educational Opportunity in Australia2015 report by the Mitchell Institute. And the

numbers are worse for those from socio-economically disadvantaged areas and

worse again for Australian Indigenous students.

26% of Australian students – more than 1 in

4 – fail to complete year 12 at school or a vocational equivalent, according to

the Educational Opportunity in Australia2015 report by the Mitchell Institute. And the

numbers are worse for those from socio-economically disadvantaged areas and

worse again for Australian Indigenous students.

26% of Australian students – more than 1 in

4 – fail to complete year 12 at school or a vocational equivalent, according to

the Educational Opportunity in Australia2015 report by the Mitchell Institute. And the

numbers are worse for those from socio-economically disadvantaged areas and

worse again for Australian Indigenous students.

Is this a failure rate that a business

would put up with? What if your business

lost 1 of every 4 of your customers a year?

Every year? Wouldn’t your

business be in crisis mode? So where is

the panic from government? Why aren’t

the customers of our education system – the students and their parents and

guardians – up in arms? And the ultimate

end-users – the businesses that need bright, creative new employees – why

aren’t they screaming for change?

How did we become so complacent about

failing the next generation of employees and employers, of entrepreneurs and

innovators?

In poorer countries, where the provision of

schooling is weak or non-existent, young people are desperate to get an

education – because education is seen as a way out of poverty and into a better

life and a better world. Why don’t young

people in affluent countries have the same vision and aspiration?

I believe it is because our education

system lacks the flexibility to teach to future needs and not to past

ideals. The world is changing – has

changed and continues to change – and schools are not keeping up.

We need a new set of values for our

education system:

1.

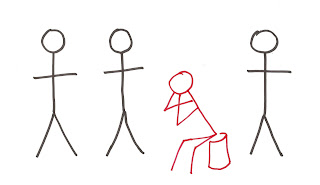

We must value diversity over

conformity.

The school

system was designed to pump out workers for the industrial revolution – people

who could all do the same job in the same way with the same level of

supervision. In the modern world we

should not only value our differences in culture, language and abilities but

also be prepared to teach in ways that allow for diverse ways of learning and

succeeding. There is no one size fits

all way of thinking, of behaving or of being – so why do we persevere with an

outmoded system that teaches to the common denominator.

2.

We must value curiosity over

obedience.

Once we dispense

with the idea of the common denominator we can allow students to follow what

interests them, allow them to investigate and to speculate, allow them to be

curious. Blind obedience is not a

desired outcome for modern businesses as we are no longer expecting the

majority of school leavers to perform identical roles to identical standards

and in identical timeframes on a factory floor.

3.

We must place diagnosis above

grading.

Rather than

using (or over-using) tests to give students grades – to pigeonhole them – we

can adopt an assessment for learning framework that uses data gathered from

student responses to tasks, activities and exercises to diagnose what has been

learned, where support is needed and where practice is required. Rather than worrying so much about where

Australians fit on the NAPLAN, or how we rank on PISA scales, let’s pride

ourselves on how we deal with students who need help.

4.

We must seek passion before

demanding delivery.

Teachers are

handed a curriculum document – essentially a list of outcomes for all students

– and expected to deliver knowledge (content) to allow students to pass tests

of whether they have absorbed the required information. Why?

Because that’s how we’ve always done it.

How many of us as adults recall all the content we were meant to have

absorbed at school? Not many! Some of us were lucky enough to have had a

teacher who ‘saw something in me’, who encouraged us in a subject that we had

an interest in, who developed our passion.

It is likely that if you are one of these lucky people that you

continued to study in a related field, or developed a skill that you used in

employment. Why isn’t this quest to

discover and develop every student’s passion the number one objective for every

teacher? I believe it is because

teachers are measured on delivery of content, judged by the grades that their

students achieve. What if we instead

trusted them to seek and develop each student’s individual talent, something

they have a passion for and encouraged them to develop skills? In my opinion we would end up with more

artists, more dancers, more engineers, more mathematicians, more designers,

more coders. And perhaps fewer generalists,

fewer drop-outs, fewer sceptics, fewer de-motivated school leavers.

Who needs to advocate this kind of

change?

We all do – parents, teachers, employers,

politicians and students.

Why?

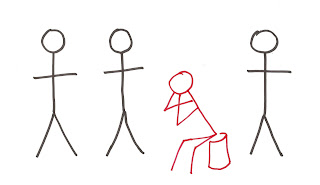

Because we are failing 1 in 4 of our

children and this is unacceptable. In

fact we may be failing more than 1 in 4 if we consider that many of the 3 in 4

do not discover their passion while at school.

Can we afford not to do this?

I’ll leave that one with you.

Comments

Post a Comment